I’ve often enjoyed snarking at James Patterson. I’m not laughing now. Because I’ve come across an item from the New York Times outlining at length the harm that James Patterson’s tactics have done to the American book world. Not just by debauching public taste. But also by forcing the revenue structures and channels of publishing to develop in new directions that have restricted opportunities for other writers and even types of writing, and have put publishers under new pressure to narrow their game. This isn’t a new article, but judging by recent developments, the situation is now even worse if anything.

I’ve often enjoyed snarking at James Patterson. I’m not laughing now. Because I’ve come across an item from the New York Times outlining at length the harm that James Patterson’s tactics have done to the American book world. Not just by debauching public taste. But also by forcing the revenue structures and channels of publishing to develop in new directions that have restricted opportunities for other writers and even types of writing, and have put publishers under new pressure to narrow their game. This isn’t a new article, but judging by recent developments, the situation is now even worse if anything.

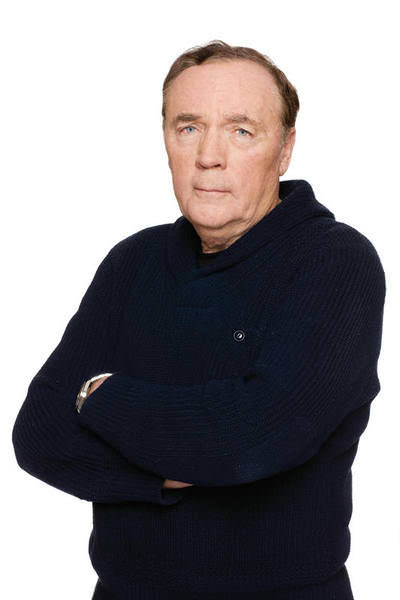

Jonathan Mahler’s deep analysis of Patterson, his co-authors, his work, and his influence isn’t necessarily critical, or toadying. And it does draw extensively on personal encounters with him. What it does very well is focus on, not Patterson the author, but Patterson Inc. the bestseller machine, and its effect on the publishing industry. And as of 2010, as the article states, one out of every 17 hardcover novels sold in the U.S. was a James Patterson title. That’s a hell of a concentration of influence in a particular business.

“Patterson has been a beneficiary of the industry’s shifting economics, but he was also a catalyst for change at Little, Brown and in the world of publishing in general,” states Mahler. Little, Brown, he points out, “was still a largely literary house” when Patterson broke big in 1993. He “almost single-handedly created a template for the modern blockbuster author.” How? “Never had authors been marketed essentially as consumer goods.” The author becomes a Fast Moving Consumer Goods brand, beholden to FMCG economics. It was an opportunity that Patterson’s career background as an ad exec at J. Walter Thompson equipped him well for. Mahler outlines how he brought the hard-sell adman’s approach into Little, Brown and quotes David Young, then CEO of Hachette, stating that “Jim is the rock on which we built this company.”

One important component of that admass approach was fighting the impression that books contained literature. Mahler again quotes one of Patterson’s former backers, this time Larry Kirshbaum, ex-CEO of Time Warner Book Group. “Jim was sensitive to the fact that books carry a kind of elitist persona, and he wanted his books to be enticing to people who might not have done so well in school, and were inclined to look at books as a headache,” says Kirshbaum. (Strange that this doesn’t seem to be such an issue in France or Germany, for instance. But I guess that’s the populist, Trump-loving Yoo Ess of Ayy for you.)

Mahler even comes out with a more reasonable explanation (than pure greed) for Patterson’s use of co-authors – who Patterson does credit, after all. “To maintain his frenetic pace of production, Patterson now uses co-authors for nearly all of his books,” Mahler explains. “This kind of collaboration is second nature to Patterson from his advertising days, and it’s certainly common in other creative industries, including television.” This also helps Patterson position himself competitively against other blockbuster authors. The point is that Patterson Inc. has created FMCG-level demand whereby a certain acreage of shelf space needs to be filled each season, and if Patterson himself can’t churn out enough words to fill that space, others are going to have to chip in to stock the supermarket shelves. Patterson Inc.’s productivity becomes hostage to its own success.

Mahler outlines the book world that the gospel according to Patterson Inc. has left us with. “Under pressure from both their parent companies and booksellers, publishers became less and less willing to gamble on undiscovered talent and more inclined to hoard their resources for their most bankable authors. The effect was self-fulfilling. The few books that publishers invested heavily in sold; most of the rest didn’t. And the blockbuster became even bigger.”

Is it fair to blame these developments all on one guy, however influential? Yes, all these potential opportunities were lying there in American bookselling and retailing already, just waiting to be exploited. But I don’t believe such changes are inevitable, and I certainly don’t believe how they develop is predetermined. America’s taste would probably have remained how it is with or without Patterson, because you can fool some of the people all of the time. But his influence has been responsible for spoiling the earth for other writers and writing, and turning traditional American publishing into something more like a monocrop ecology, where only one species dominates and the rest clings to survival along its fringes.

Meantime, if Patterson Inc. is partly responsible for creating this ecosystem, Patterson’s donations to indie bookstores and so on only go the shortest distance towards undoing the damage. And it’s perhaps a blessing, but no surprise, that Amazon has come along and refragmented demand, so that FMCG-style passive-consumer demand economics no longer have such power over the suppliers. No wonder the Big Five who grew Big off Patterson Inc.-style big-box marketing are now struggling to hold up their share of sales. Thank Patterson Inc. for that.